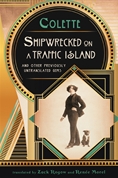

We’ve had no new Colette translations in English for fifty years. It’s a startling fact, if somewhat disputable: Robert Phelps translated many of her letters for 1980’s Letters from Colette. It’s possible translators Zack Rogow and Renée Morel, they of a new Colette volume from SUNY Press/Excelsior Editions, are referring only to work she intended for publication. There have been biographies (Gillian Gill’s Becoming Colette is the most recent on that score) and a cultural history (Patricia A. Tilburg’s Colette’s Republic, which considers the writer as a central figure in France between 1870 and 1914). The lack of translations isn’t due to a lack of opportunity. Of the fifty-plus books Colette published during her lifetime, probably no more than half have been translated into English. That drought ends with Shipwrecked on a Traffic Island: And Other Previously Untranslated Gems. The subtitle is altogether appropriate.

When she was twenty years old, Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette married Henri Gauthier-Villars, a man better known as Willy. He was in his early thirties and ambitious in his way, though his shamelessness was a more defining trait. This was 1893. The couple set up house in Paris. It was his lot to be a writer, or so Willy believed. Years after they parted, Colette observed that, “He must, in the old days, have often believed that he was on the point of writing, that he was about to write, that he was, in fact, writing. And then, as he felt the pen within his fingers, there would come a slackening, a collapse of the will, and his illusion vanished.”

Willy was nothing if not resourceful. Colette had told him stories of her girlhood, and he suggested that his young wife write some of them. He made editorial suggestions and eventually concluded the stories stood more chance of success with his name on them. His instincts about the stories’ potential was sound. The first of the four Claudine novels, Claudine at School, appeared in 1900. Willy grew famous off them, as did Claudine. A perfume appeared in her name, as well as an ice cream flavor and a brand of cigarettes, among other items. Colette benefitted less. The writer Glenway Wescott notes that Willy, “locked her in her room for four hour stretches while she inked up a certain number of pages with her heaven-sent and profitable phrases, sentences, paragraphs.” In return, she was able to send small gifts to her mother. It placated her temporarily, but the arrangement wasn’t destined to last. By 1904, Colette was publishing work as Colette Willy. Two years later, they divorced. Willy faded into obscurity. Colette became one of the great writers of the century.

She’s long been celebrated as unsentimental, and it’s not hard to imagine that disposition had roots in her years with Willy. “Look for a long time at what pleases you,” she’s said to have told a young writer, “and longer still at what pains you.” It was also Colette who told the young Georges Simenon to remove anything literary from his work. His romans durs are testament to the soundness of that advice. Time and again Colette heeds these words in her own work. In “The Little Bouilloux Girl,” she shows us a beautiful young woman in a provincial town, intent on waiting for the dashing stranger fate will surely provide to carry her away. He never arrives, and she ends up with a life of solitude, far from the bright lights. “Bella Vista” begins, “It is absurd to suppose that periods empty of love are blank pages in a woman’s life.” Impossible as it seems, the remainder of the story rises to the level of that opening line.

The newly translations seem slighter at first glance. They’re selections are from her journalism and occasional pieces in many cases, but her mark on the least of them is unmistakable. They aren’t sustained narratives, but they accumulate in the service of a single, great subject. Colette wrote about all of life, without illusions. In “Letter to My Daughter,” she writes of, “an attitude that certain of my novels take on. A little attitude – bless their hearts! – of true modesty, and it suits them rather well.” The same might be said of the offerings in Shipwrecked on a Channel Island. She’s fond and irreverent in an essay on women growing older. In a brief note on the doll maker Madame Le Minor comes this carefully calibrated, knowing line: “Possession – a marvelous, brutal, and complete education, uses touch in tandem with sight and the imagination, and chooses its moment.” The ground she covers can seem familiar to readers of her work, but she distills her thoughts still further and offers five-hundred words on the morning light, five hundred on jealously, a thousand on the silence of small children. There are sketches here on a par with the best of Joseph Roth’s feullitons (collected, by the way, in What I Saw: Reports from Berlin 1920-1933 and Report from a Parisian Paradise: Essays from France, 1925-1939).

She knows the value of never revealing too much, or only doing so strategically. This suits both the chosen form and her talents as a writer. Her eye seems always to alight on the most telling detail -the shade of a leaf in the day’s first light; the quality of a movement; a voice’s inflection. Even entries from her advice column are better than mere curiosities. Her opinions are direct and unwavering, almost epigrammatic at times. To a young woman worried by the fact she’s more attracted to another man than to her fiancé, Colette writes, “Leave him be, the angel; and leave the tempter. Does my response not bring you the ‘peace’ you crave? Excuse my frankness, but I can’t help remembering that you are twenty years old. And I’ve never been able to believe that peace is a good present to give a young woman.”

Colette was a child of nature. She offered the world her great, pagan heart and her unsparing view of its failings. It was a sustained gift, a sustaining gift, one we’ll not soon see the likes of again.

— John McIntyre