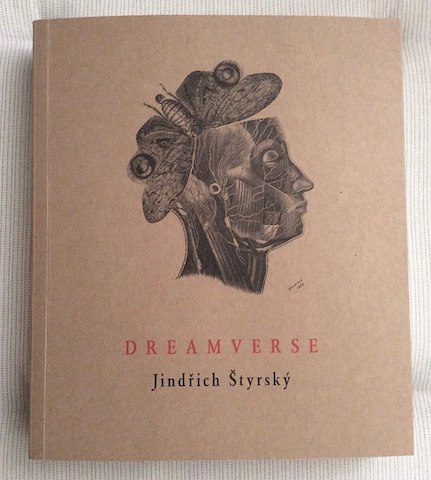

There are certain books you know almost at once you will keep, always. Some years you might not encounter a single one. Others you’ll find half a dozen. These aren’t always rare editions. For years, I’ve held onto a worn copy of The String of Pearls by Joseph Roth that I bought in Seoul, at a little English language bookshop, uphill from the subway stop at Itaewon, not far from the military base. I’d say the same about a thick, handsome omnibus of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria Quartet I picked up in Australia a dozen years ago and have lugged around with me ever since. The most recent addition to this slow-growing, ad hoc canon is Jindřich Štyrský’s Dreamverse, a hybrid creation filled with Štyrský’s art, poetry and retellings of his dreams.

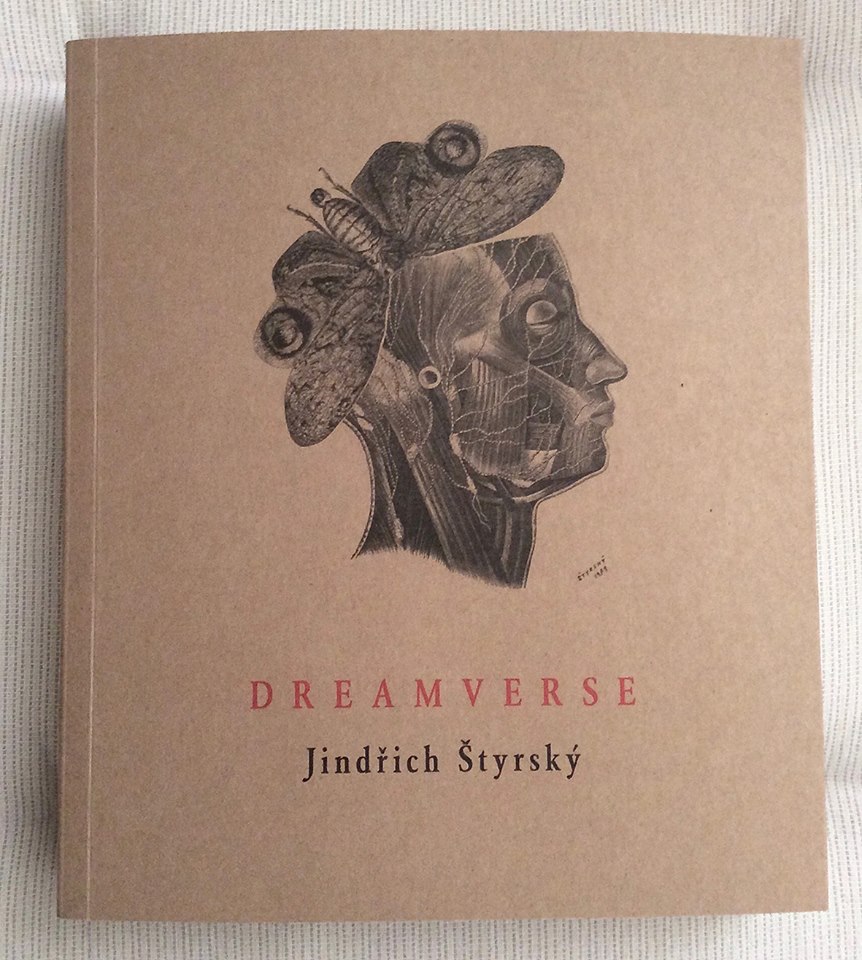

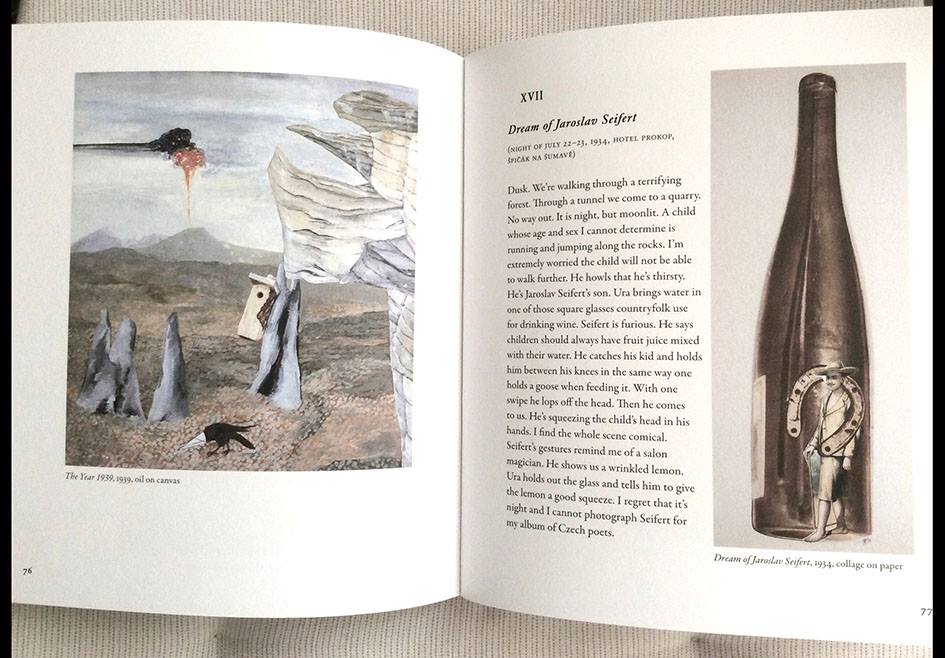

If that sounds tedious or self-indulgent, it’s in fact neither. It’s said that Štyrský was “influenced by Max Ernst’s collage-novels and André Masson’s illustrations for Aragon’s and Bataille’s erotic writings,” and what he made from those influences, plus his own talent, does credit to all involved. Štyrský is as compelling as Magritte in Melancholy (1937) and Mayakovsky’s Vest (1939).

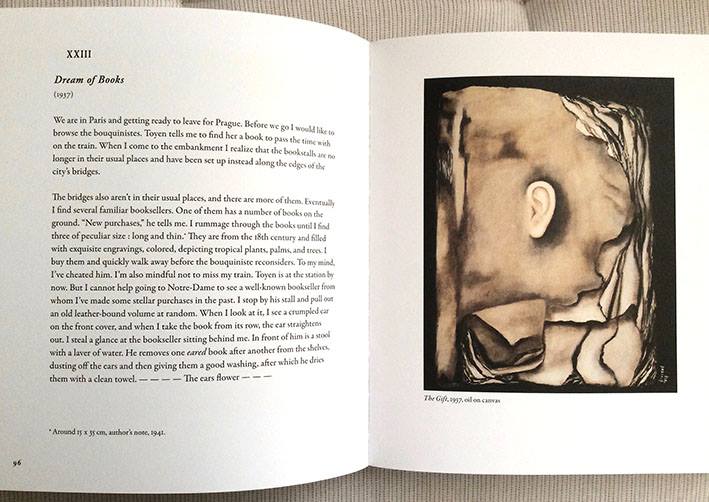

“Dream of Books” would do Calvino proud with its romance, and the ease with which he unsettles the settled world without for an instant causing the reader to wish to withdraw. There is, in fact, a tantalizing logic to the new arrangement in Štyrský’s dream. “We are in Paris and getting ready to leave for Prague,” Štyrský writes. “Before we go I would like to browse the bouqinistes. Toyen tells me to find her a book to pass the time with on the train. When I come to the embankment I realize that the bookstalls are no longer in their usual places and have been set up instead along the edges of the city’s bridges.”

In an introductory essay to the book, the artist Karel Teige, a peer and compatriot of Štyrský’s, writes that, “Reality as depicted in paintings that copy nature is of life enfeebled and emasculated. And Štyrský does appear to aim for something heightened, some transcendent understanding, in his work, both written and visual. The Year 1939, for example, has an echo of the apocalyptic, of high and inescapable stakes, yet it somehow presents as matter of fact. It’s Štyrský at the height of his powers, a mere three years before his death.

It seems to me that Jindřich Štyrský is too little known in the English speaking world. That’s a shame, I’d say – you might’ve guessed by the fact I’m writing about him – and this new edition of Dreamverse makes a startlingly strong case for that opinion. New York’s Ubu Gallery presents his work regularly enough, lends it out to other institutions when possible, and published a catalog entitled Jindřich Štyrský: Emilie Comes to Me in a Dream, to accompany a 1997 exhibition. If it’s the legacy institutions whose stamp of approval will do it for you, his work is in the permanent collections of the Tate and MoMA, just for instance. You can even pick up a piece of his work from Hundertmark Gallery, if you can afford to splash out a bit. But it’s Twisted Spoon Press, a small and discerning publisher located in the Czech Republic, who’s responsible for this rich new Štyrský volume. I can’t speak to the size of the print run, or whether there’s likely to be an additional printing, but it’s without question one of the finest projects I’ve encountered from any publisher, large or small, in recent years. It’s also not the only Twisted Spoon title worth owning; they’ve got a pair of Bohumil Hrabal titles on their list, just as a beginning, as well as Joshua Cohen’s The Quorum and a volume by Péter Nádas. And the Image to Word series, of which Dreamverse is a part, is altogether irresistible. Publishing can so often seem predictable and risk averse, but there are always exceptions. Dreamverse for me holds a place of prominence on that list.